Impact in brief

IAS is personally relevant to students and their lives, elicits and values students’ questions and experiences, and provides support for building some of the dimensions of science capital.

Together, its various elements create an environment in which students are able to contribute from their own interests and experiences.

Consequently, through participating in IAS, students can come to see science as more personally relevant to them and to appreciate that scientists are ‘normal people’. Moreover, ultimately it is the participating students who are in control in I’m a Scientist — it is their votes that determine the winner.

This environment, we believe, reinforces that the ‘field’ of I’m a Scientist is one in which it is students’ valued and valuable opinions that count the most.

Together, then, the elements of IAS can support students’ science capital, meaning IAS can play an important role in helping young people see that science just might be ‘for me’. This, in turn, can contribute to nurturing science aspirations.

Supporting the Science Capital Teaching Approach

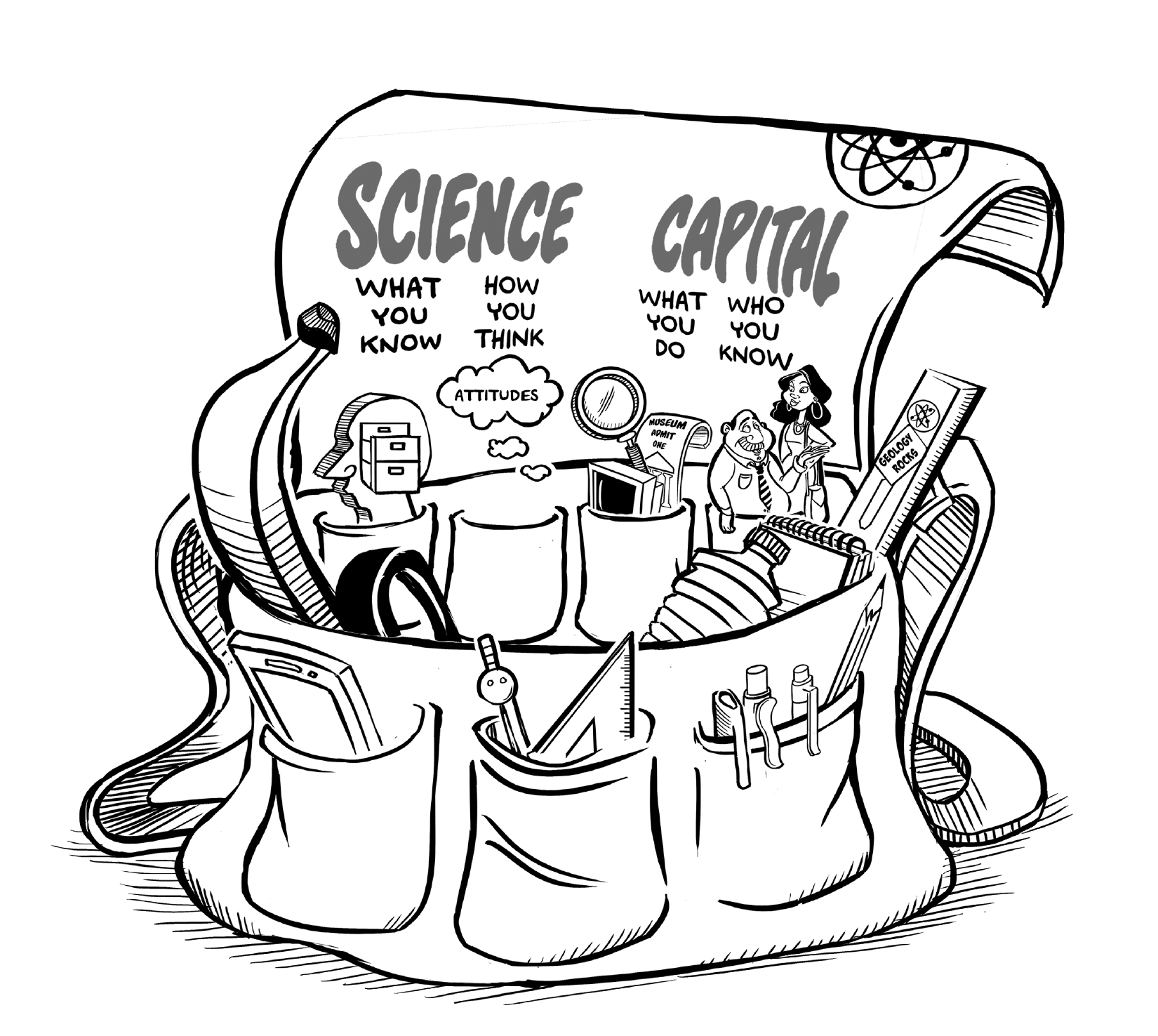

Science capital is a set of resources that helps individuals engage and identify with science. Young people with higher levels of science capital are more likely to see science as ‘for me’ and to choose to study science subjects at a higher level.

The Science Capital Teaching Approach (Godec, King, & Archer, 2017) aims to enhance young people’s engagement with science, supporting them in seeing science as relevant to their lives and ‘for me’.

The foundation of this approach involves broadening what counts in the science classroom: creating a learning environment where all students feel able to offer contributions from their own experiences and interests. The approach also consists of three main pillars:

- Personalising and localising: Going beyond contextualising, to connect to the actual experiences, understandings, attitudes and interests of young people.

- Eliciting-valuing-linking: Inviting students to share knowledge, attitudes and experiences; recognising these has having value; and connecting this back to the science.

- Building the dimensions of science capital: Considering the eight dimensions when developing activities, lessons or programmes.

Evaluating the I’m a Scientist experience for students

Dr Jen DeWitt, an Associate Senior Research Fellow on the core Science Capital team, has conducted an evaluation of I’m a Scientist to see how the experience might support students’ science capital.

The research consisted of student focus groups, teacher interviews, surveys and analysis of content generated on the IAS site including transcripts of live chats and questions asked by students. Read about why we took this approach.

The evidence produced by this research demonstrates that the experience of IAS maps onto elements of the Science Capital Teaching Approach. In turn, this supports science capital-related outcomes of participating in IAS.

Report summary: Supporting science capital dimensions

The research found evidence that I’m a Scientist provides support for four of the science capital ‘dimensions’:

- Dimension 1: Science literacy;

- Dimension 2: Seeing science as relevant to everyday life;

- Dimension 3: Knowledge about the transferability of science/science qualifications; and especially

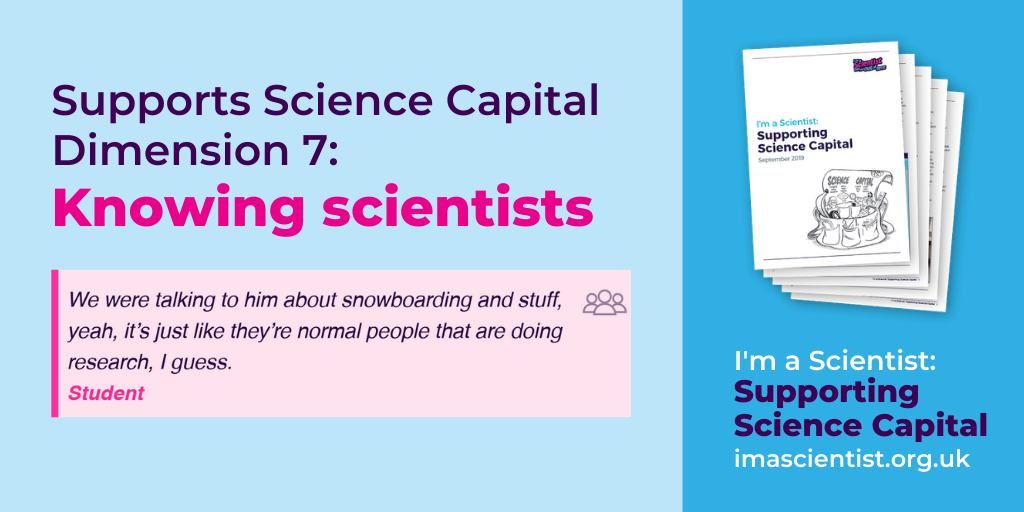

- Dimension 7: Knowing people in science-related jobs.

Although we acknowledge that ‘meeting’ scientists in IAS is not the same as having personal relationships with them, we believe that the experience of IAS provides support for similar outcomes to knowing people in science-related jobs — understanding what it’s like to work in those jobs and, even more importantly, coming to see scientists as ‘normal’ people.

Research shows that this understanding — which is abundant in young people who have friends or family working in science — facilitates a sense that science is ‘for me’ and makes it more likely that an individual can envisage being a scientist as a possibility for themselves. Consequently, developing or maintaining aspirations in science can become more likely.

IAS is a relatively brief enrichment experience and cannot be exclusively responsible for developing students’ science aspirations and maintaining a sense that science is ‘for me’ over time. However it has a valuable role to play in contributing to this process, especially for young people who may simply not have other opportunities to encounter people in science-related roles, much less to ask them questions of personal interest and relevance. And, indeed, our data suggest that IAS does have the potential to support or nurture science-related aspirations in participating students.

In this report, we explore in detail how IAS may support students’ science capital using the Science Capital Teaching Approach (Godec, King, & Archer, 2017) as a lens through which to consider the various elements of IAS. Applying an SCTA lens to IAS has helped us understand the outcomes we observed, as well as what elements of IAS may be contributing most strongly to them.

Considered in this way, IAS seems distinctively suited to support the development of science capital. Its whole premise — from who is encouraged to participate (e.g. widening participation and underserved schools) to the nature of the activity itself — is that of creating a learning environment where young people have the opportunity to contribute by drawing on their own experiences and interests (‘broadening what counts’).

More specifically, in live CHATs and in ASK, young people are invited to contribute questions (‘elicit’). Scientists value these questions by responding — often in considerable detail. And the focus of each zone on areas of science often links these questions back to science content. Because students are in control and ask questions of interest to them (they are the ones deciding what to ask), the events are necessarily personalised and localised.

IAS also supports the development of dimensions of science capital.

By providing the opportunity to ask about science content, it contributes to science literacy (Dimension 1).

Because students can ask questions of interest to them personally, it can enhance science-related attitudes and values, helping students to see science as relevant to their everyday lives (Dimension 2).

When students ask about qualifications, participation may improve their knowledge of the transferability of science (Dimension 3).

Most importantly, however, IAS provides an opportunity to get to know scientists (Dimension 7) — about the paths they took to their current work, about a range of aspects of their work (e.g. travel, teamwork) and about their lives outside of work. Students may even discover that scientists are not all ‘super geniuses’ — that they are normal individuals, albeit with interesting jobs.

In sum, IAS is personally relevant to students and their lives, elicits and values students’ questions and experiences, and provides support for building dimensions of science capital. Together, its various elements create an environment in which students are able to contribute from their own interests and experiences.

Consequently, through participating in IAS, students can come to see science as personally relevant to them and to appreciate that scientists are ‘normal people’. Moreover, ultimately it is the participating students who are in control — it is their votes that determine the winner.

This environment, we believe, reinforces that the ‘field’ of I’m a Scientist is one in which it is students’ valued and valuable opinions that count the most. Together, then, the elements of IAS can support students’ science capital, meaning IAS has an important role in helping young people see that science just might be ‘for me’ which, in turn, can contribute to nurturing science aspirations.

To find out more detail on how IAS maps on to the Science Capital Teaching Approach: